blueant kirjutas:Loogiliselt mõeldes pole võimalik, et Euroopa riigis on sadu tuhandeid inimesi, keda politsei, kelle kasutada on kõik andmebaasid ja öised reidid (neid Saksas tehakse), leida ei suuda.

Sajad tuhanded küll, aga rahvaarv on ka ligi 83 M. Leidmise puhul on muidugi asi motivatsioonis & rahastatuses.

Allpool on FT artikkel samal teemal. Siin räägitakse teadmata rahvastikust hinnangulises suurusjärgus alates 1,9 M Euroopa peale 2008. aastal. Protsentuaalselt on see umbes sama kui 300 000 tänapäeva Saksamaal - ja vahepeal on teatavasti üht-teist toimunud ka.

Migration: the riddle of Europe’s shadow population

The number of undocumented migrants in the EU is unknown but some cities are realising that ‘get-tough’ policies do not work

Michael Peel in Barcelona and Jim Brunsden in Brussels October 7, 2018

Lennys fled her native Venezuela a decade ago as trouble brewed during the later years of former president Hugo Chávez’s rule. Her father died at the hands of a criminal gang as a full-blown economic and political crisis loomed. She travelled to Barcelona on a tourist visa to join a friend, and never returned.

Now in her mid-forties, Lennys has lived in what migration experts call “irregular” status ever since, without official permission to stay. Once a human resources manager in her homeland, she has worked in the Catalan capital mainly as a maid, boosting her income of about €700 a month with piecemeal jobs paying €35-€40 a time.

She is not alone. Lennys — not her real name — is part of a shadow population living in Europe that predates the arrival of several million people on the continent in the past few years, amid war and chaos in regions of the Middle East and Africa. That influx, which has fuelled Eurosceptic nativism, has if anything complicated the fate of Lennys and other irregular migrants.

Now she is using a service set up by the Barcelona local administration to help naturalise irregular migrants and bring them in from the margins of society. She is baffled by the anti-immigrant rhetoric of politicians who suggest people like her prefer living in the legal twilight, without access to many services — or official protection.

“I think there is a minimum as a human being you should be entitled to,” she says, in an interview in the local administration offices, a stone’s throw from the tourist throngs of Plaza de España. “I suggest the leaders of these parties try living as an irregular migrant in another country some time.”

The fate of Lennys and other irregulars is likely to take an ever more central role in Europe’s deepening disputes on migration. They are a diverse group: many arrived legally, as Lennys did, on holiday, work or family visas that have since expired or become invalid because of changes in personal circumstances. Others came clandestinely and have never had any legal right to stay.

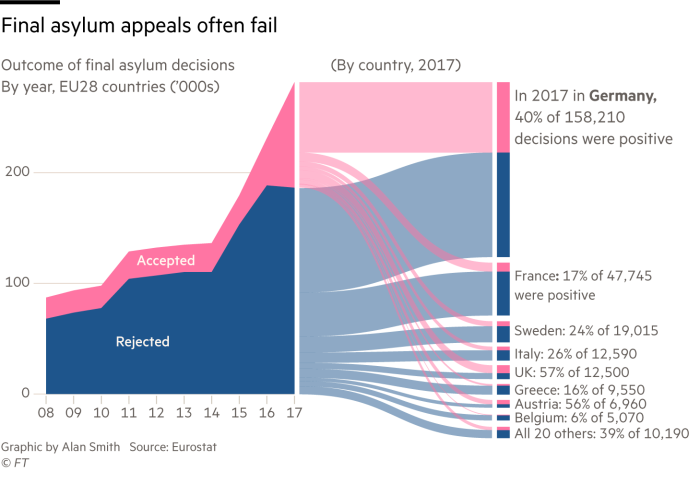

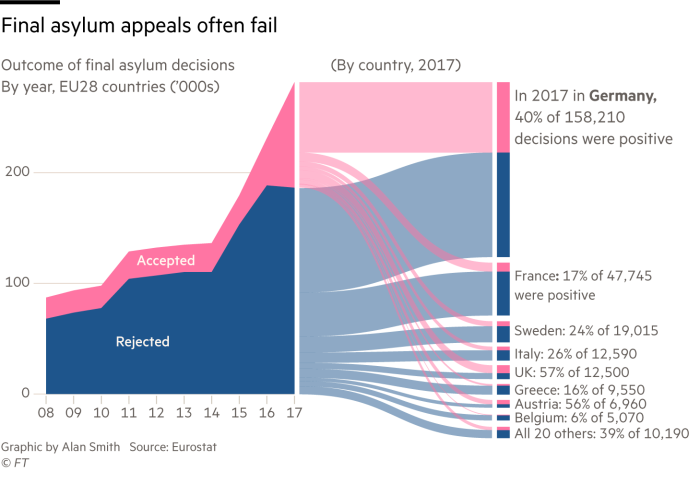

The most scrutinised, and frequently demonised, cohort consists of asylum seekers whose claims have failed. Their numbers are growing as the cases from the surge in migrant arrivals in the EU in 2015 and 2016 — when more than 2.5m people applied for asylum in the bloc — work their way through the process of decisions and appeals. Almost half of first instance claims failed between 2015 and 2017, but many of those who are rejected cannot be returned to their home countries easily — or even at all.

The question of what to do about rejected asylum applicants and the rest of Europe’s shadow population is one that many governments avoid. Bouts of hostile rhetoric and unrealistic targets — such as the Italian government’s pledge this year to expel half a million irregular migrants — mask a structural failure to deal with the practicalities.

The last thing they want to admit to is that there is a population of people who are not only undocumented, but also uncountable and often unreportable.

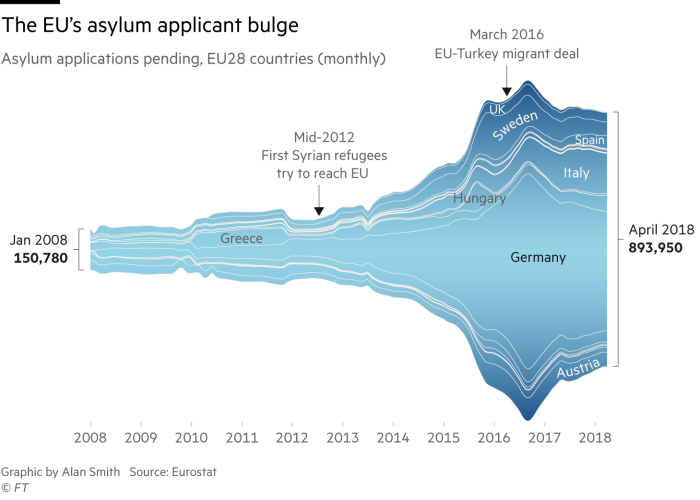

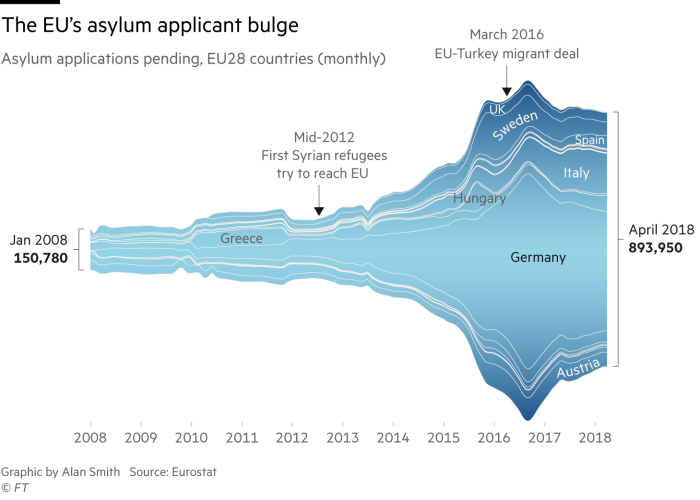

The management of migration has come to dominate national elections and the EU agenda. It will be discussed again at a gathering of leaders in Brussels on October 18, even though fewer than 100,000 people have arrived in the EU via the Mediterranean Sea this year, compared with more than 1m in 2015. That fall is partly due to a 2016 deal under which the EU agreed to pay Turkey an initial €6bn to take back people who travel from its territory to the Greek islands.

Many governments have sought to deny irregular migrants services and expel them — policies that can create their own steep human costs. But authorities in a growing number of cities from Barcelona to Brussels have concluded that the combination of hostile attitudes and bureaucratic neglect is destructive.

These cities are at the frontline of dealing with irregular status residents from Africa, the Middle East and elsewhere. Local authorities have, to varying degrees, brought these populations into the system by offering them services such as healthcare, language courses and even legal help.

The argument is part humanitarian but also pragmatic. It could help prevent public health threats, crime, exploitative employment practices — and the kind of ghettoisation that can tear communities apart.

“If we provide ways for people to find their path in our city . . . afterwards probably they will get regularisation and will get their papers correct,” says Ramon Sanahuja, director of immigration at the city council in Barcelona. “It’s better for everybody.”

The size of Europe’s shadow population is unknown — but generally reckoned by experts to be significant and growing. The most comprehensive effort to measure it was through an EU funded project called Clandestino, which estimated the number of irregular migrants at between 1.9m and 3.8m in 2008 — a figure notable for both its wide margin of error and the lack of updates to it since, despite the influx after 2015.

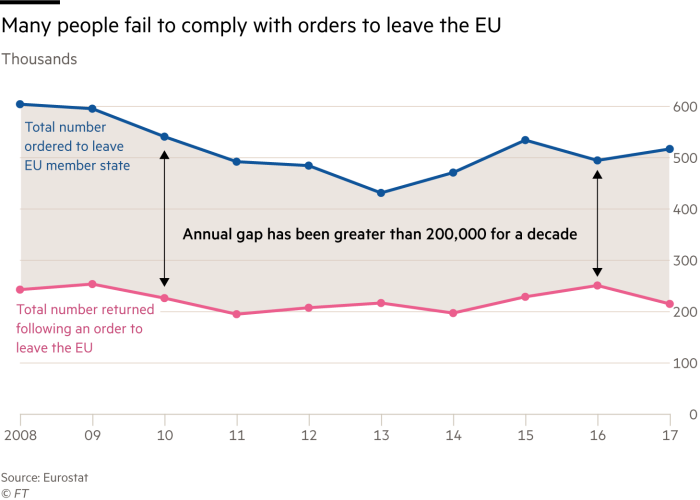

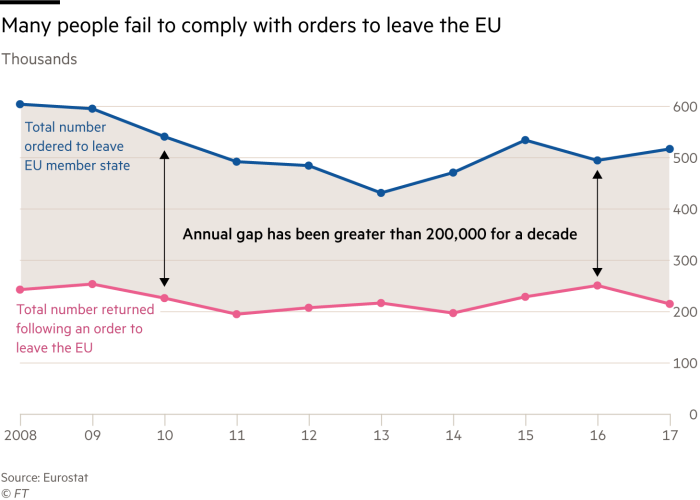

A more contemporaneous, though also imprecise, metric comes from comparing the numbers of people ordered to leave the EU each year with the numbers who actually went. Between 2008 and 2017, more than 5m non-EU citizens were instructed to leave the bloc. About 2m returned to countries outside it, according to official data.

While the two sets of numbers do not map exactly — people don’t necessarily leave in the same year they are ordered to do so — the figures do suggest several million people may have joined Europe’s shadow population in the past decade or so. The cohort is likely to swell further as a glut of final appeals from asylum cases lodged since 2015 comes through.

This partly helps explain why the EU is focused on improving its return rate of irregular migrants to their home countries, which officially fell from 46 per cent in 2016 to 37 per cent last year. While the obstacles to repatriation are sometimes legal — because some countries of origin are deemed unsafe — they are more often practical. People’s countries of origin often refuse to accept them, because they have no documents or authorities dispute whether their papers are genuine. The migrants can neither move forward into the EU nor go home: they have nowhere to go.

“The volume of people who are in limbo in the EU will only grow, so it’s really problematic,” says Hanne Beirens, associate director at Migration Policy Institute Europe, a think-tank. “While the rhetoric at a national level will be ‘These people cannot stay’, at a local community level these people need to survive.”

Serge Bagamboula at a rally in Brussels

When Serge Bagamboula travelled to Brussels on a student visa in 2009, he never imagined that 10 years later he would be living in the country illegally. The 56-year-old came to Belgium from his native Congo-Brazzaville to study for a masters degree at the Université libre de Bruxelles. But, once his course finished, a deteriorating political situation and few job prospects at home convinced him to stay. Now he is part of an organised movement of Belgium’s undocumented workers — known as sans papiers — who are seeking more rights and greater recognition of their economic contribution.

“The powers that be cannot simply ignore us,” he says, speaking in a coffee shop at Brussels’ Gare du Midi station, from where train routes fan out across Europe. “We need regularisation.”

The Belgian government does not release estimates of the number of undocumented migrants in the country, but non-governmental organisations put the figure in the hundreds of thousands. Brussels is a focal point. Its status as a highly international city — one of its 19 districts records people from more than 100 countries — contributes to making it a natural destination for young people looking for opportunities.

Fairwork Belgium, an organisation that helps to protect sans papiers from exploitative employers, is contacted by hundreds of undocumented workers every year, many of them Brazilians and Moroccans. Jan Knockaert, co-ordinator at Fairwork, says he has even handled cases for construction workers who helped to build the EU’s headquarters. “Undocumented workers have been involved in building the new European Council building and the crèche of the European Parliament, as well as cleaning the [Belgian] Palais de Justice,” he says.

Belgian policy towards irregular migrants and undocumented workers has stiffened under the current government, which includes the hardline Flemish nationalist NVA party. It has prioritised the expulsion of “transmigrants”— the term used for people that have travelled to Europe, often via north Africa and the Mediterranean and that are seeking to move on from Belgium to other countries, notably the UK. Several hundred live rough in and around Brussels’ Gare du Nord.

“We have a lot of failed asylum claims and asylum seekers trying to go to the UK,” says Theo Francken, the Belgian immigration minister. “And that’s what we see on the streets and the highways”.

Forced returns of irregular migrants in Belgium rose from 8,758 in 2014 to 11,070 in 2017. Construction sites and night shops — stores with long opening hours — have been among the targets for visits by the labour inspectorate.

The NVA has proposed in parliament that there should be no repeat of the kind of general amnesty of sans papiers that took place in Belgium between 1999 and 2002. Belgian law guarantees irregular migrants urgent medical care, while some basic labour rights are enshrined in European law. The children of sans papiers are also eligible to attend state schools. Regional administrations in the country fund associations that help undocumented workers learn skills and find housing.

Mr Bagamboula’s activities include working with local government to free up unused housing for use by sans papiers, and projects to increase the independence of migrant women. “We want to show that we are people who you see every day, who help to build the country, whose children are at school with your children,” he says.

He describes life for irregulars in Belgium as one of constant uncertainty: unable to open bank accounts or present official documents, they can find themselves having to shift every couple of weeks from one temporary accommodation to the next.

“People talk about a migration crisis, but it’s really a reception crisis,” Mr Bagamboula says of what he sees as the shortcoming in Belgium’s management of irregular migration. “The migrants of today are the sans papers of tomorrow”.

It is a tricky long-term reality the EU and its member states face. A significant shadow population is already in the bloc and, available data would suggest, increasing.

Lennys’ status in Barcelona has changed since she arrived 10 years ago. She has a work permit and is paying taxes. She gets free healthcare and has done a Catalan language beginners’ course for free.

She argues that if governments see irregular migrants simply as a political problem, they will get it wrong. Harsh treatment, or simply abandonment, are not only unjust, she says, but also self-defeating for both EU countries and the communities hosting these precarious populations.

“It’s not fair for people who want to bring something positive to society,” she says as the waiting room below fills with dozens of her peers also in search of a status.