NATO muutusest tänu Ukraina sõjale. Kui enne oli plaanides, et võib mõne ala okupeerida lasta siis nüüd kaitstakse territooriumit esimeste meetrite pealt. Selleks liigutatakse Ida-Euroopasse juurde vägesid ja tehnikat ning varustust.

NATO is rapidly moving from what the military calls deterrence by retaliation to deterrence by denial. In the past, the theory was that if the Russians invaded, member states would try to hold on until allied forces, mainly American and based at home, could come to their aid and retaliate against the Russians to try to push them back.

But after the Russian atrocities in areas it occupied in Ukraine, from Bucha and Irpin to Mariupol and Kherson, frontier states like Poland and the Baltic countries no longer want to risk any period of Russian occupation. They note that in the first days of the Ukrainian invasion, Russian troops took land larger than some Baltic nations.

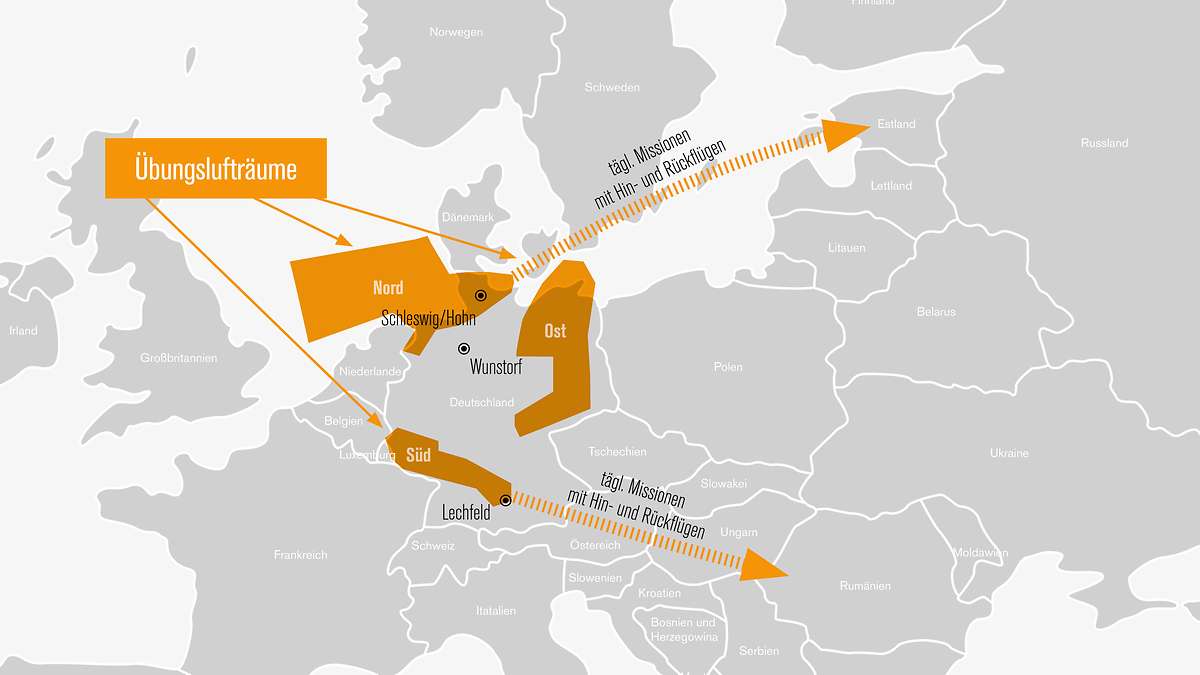

To prevent that, to deter by denial, means a revolution in practical terms: more troops based permanently along the Russian border, more integration of American and allied war plans, more military spending and more detailed requirements for allies to have specific kinds of forces and equipment to fight, if necessary, in pre-assigned places.

The alliance will put more troops under the direct control of NATO’s top military officer, the supreme allied commander Europe, Gen. Christopher G. Cavoli, who also commands American forces in Europe.

Under a new rubric of “deter and defend,” General Cavoli is for the first time since the Cold War integrating American and allied war-fighting plans, a senior NATO official said, speaking anonymously because of the topic’s sensitivity. Americans are back at the heart of Europe’s defense, he said, deciding with NATO precisely how America will defend Europe.

For the first time since the Cold War, the official said, East European countries will know exactly what NATO intends to do to defend them — what each country should be able to do for itself and how other countries will be tasked to help. And Western countries in the alliance will know where their forces need to go, with what and how to get there.

NATO is also aligning its longer-term demands from allies with its current operational needs. If in the past NATO countries might be asked to send some lightly armed expeditionary forces with helicopters to Afghanistan, for instance, now they will be tasked to defend particular parts of NATO territory itself.

Right now there are major post-Cold War roadblocks that include lack of storage, lack of suitable rail cars, lack of emergency rights of way to cross borders and use of roadways, issues that involve decisions by civilian authorities.

But even supplying Ukraine from a peaceful Poland is proving a major logistical headache, said another NATO official, who also spoke on the topic under condition of anonymity. Trucks are backed up with supplies, there’s a shortage of railway cars that can carry heavy equipment like tanks, and permissions must be obtained at every European border. Doing it in a shooting war, he said, with missiles flying, bombs dropping, the internet crashing and refugees racing in the other direction, is another challenge entirely.

“NATO didn’t think seriously about defending its own territory and now it must,” said Mr. Daalder, president of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. It did that for 40 years, and even if the muscles have atrophied, the muscle memory is there, he said. “The key is to have people and governments who never lived through this, learning how to do it.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/17/worl ... d=tw-shareAinus, mida me ajaloost õpime, on see, et keegi ei õpi ajaloost midagi.

Live for nothing or die for something.

Kui esimene kuul kõrvust mõõda lendab, tuleb vastu lasta.

EA, EU, EH